Data is an important weapon in the fight against antimicrobial-resistant bacteria, but collection in the Atlantic provinces has stalled

The global issue of antibiotic resistance, more accurately called antimicrobial resistance (AMR), can be overwhelming. Often people feel there’s nothing they can to do to change the situation one way or another. But with the severe impacts of AMR on human health, scientists are calling for more data to understand the issue, whether it’s on antibiotics being administered to humans or to livestock animals.

Tracking administration of antimicrobials and studying AMR in livestock at farms, at abattoirs and at retail locations is vital to understand all of the factors that may be contributing factors.

There are many groups involved with decisions regarding treatment of an animal: the front line farmers and employees who care for the animal and usually administer the drug, the veterinarian who prescribes it or the retailer that carries medicated feed if it is over-the-counter, and the livestock commodities (e.g. Dairy Farmers of Canada, the Egg Farmers of PEI, PEI Hog Marketing Board) who create and/or oversee the quality assurance programs their members must adhere to.

It can be an overwhelming maze of national and provincial regulation, industry self-regulation, provincial, federal suggestions and guidelines through to laws.

Different sectors are making changes to their methods in an attempt to manage the issue. The livestock commodity boards are tightening their quality assurance programs and new federal regulations will require veterinary oversight for antimicrobials used on food animals, including those administered in feed or water. Prince Edward Island’s Veterinary Medical Association (PEIVMA) updated their Continuing Education Policy as recently as November 2016 to reflect a larger component dealing specifically with AMRs.

But the issue remains – Canada has no top-level strategy of oversight and reporting across all of the facets involved in AMR management. According to an article in the Canadian Medical Association Journal May 2014, experts in the field saw Canada’s need for an umbrella strategy for many years.

“‘Overarching problems with [existing] programs is their susceptibility to budgetary cuts and their piecemeal approach’, says Dr. John Conly, professor of medicine at the University of Calgary in Alberta. For more than a decade, experts have been calling for a more coordinated national system ‘with the true leadership being shown by the federal level.’”

Dr. Conly’s words went from cautionary to prophetic for Atlantic Canada in 2015’s mid-election budget cuts.

“[For seven years] we monitored for certain bacteria and their antimicrobial resistance on specific cuts of meat at retail stores around the Maritimes for Canadian Integrated Program for Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance (CIPARS). And in the span of a few weeks, our project was completely shut down,” said Dr. J. Trenton McClure, Professor of Large Animal Medicine at Atlantic Veterinary College (AVC) in an interview with Salty.

McClure was referring to research executed by the College on behalf of the Public Health Agency of Canada’s program, CIPARS. AVC was contracted in 2008 to collect data in the Maritimes, but their part was cancelled abruptly in July 2015, with six months left in the contract. Surveillance of AMR in retail meat in the Maritimes has not resumed since then.

In an email to Salty, PHAC wrote “…CIPARS has been tracking antimicrobial use and antimicrobial resistance (AMR) along the food supply chain since 2002. The program collects data on farms, at abattoirs and at retail locations in several regions of Canada. Under this program, clinical isolates of Salmonella from humans and animals are also tested for AMR.

“Each year, priorities for data collection are established and surveillance activities are reviewed to ensure consistency with these priorities. In 2015, collection of data from retail locations in the Atlantic provinces was discontinued, with resources redirected to support other surveillance activities. At the present time, there are no plans to resume this activity.

“The Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA) conducts retail monitoring in locations including the Atlantic provinces, but does not test for AMR. The Public Health Agency of Canada is unaware of any retail sampling being conducted for the purposes of AMR testing at the provincial level in the Atlantic provinces.”

“We were starting to see important trends in the AMR data” Dr. McClure said. These statistical trends are the vital information needed by scientists studying food safety. Without reliable data, it is difficult to make recommendations on how to keep antimicrobial resistance low.

“These type of surveillance programs, along with improved data collection on antimicrobial use in animals is essential to identify changes in AMR and the impact of changes in antimicrobial use perhaps through new regulations has on resistance patterns,” he said.

He emphasized the importance of having sound information when deciding how and when medicate animals.

Could an outright ban of use of antibiotics in livestock animals be a solution? According to Dr. McClure, this is not a simple cut-and-dried issue.

“It remains a question of being able to look after an animal’s welfare,” he said. He also mentions that a lot of attention is given to animals destined for the table, but vital information about companion animals (e.g. dogs and cats) is often exempted from data sets.

Without good data collection and information on antimicrobial resistance and use available to scientists and policy makers it is difficult to make scientifically sound decisions.

Most of Canada’s oversight of AMRs in both humans and animals is at a federal rather than provincial level. And despite predictions of an overall strategy being released in December 2016, Canadians are still waiting for the federal government to release their new plan.

“Any plan put forward should adequately represent all regions and all peoples of Canada including more rural regions, such as Atlantic Canada and indigenous communities,” Dr. McClure said.

What happens when we don’t have enough data?

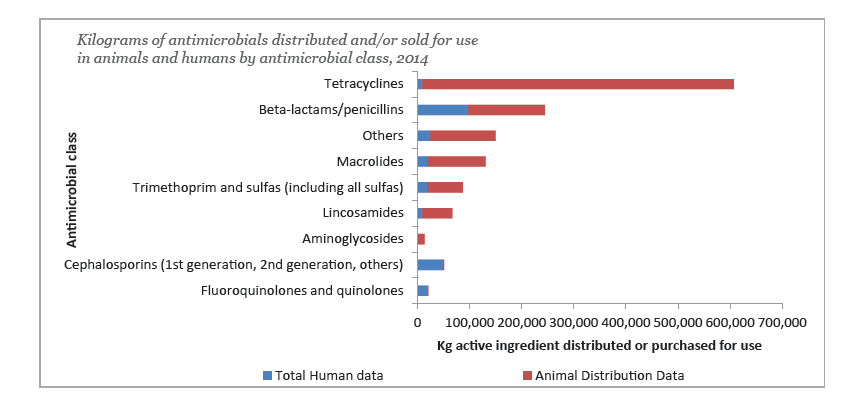

Source: Canadian Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance System (CARSS) – Report 2016

“The graph used in January’s Salty [referring to our reprint of Kilograms of Antimicrobials distributed and/or sold for use in animals and humans by antimicrobial class, 2014, from the Canadian Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance System (CARSS) – Report 2016, pictured below] is misleading.”

Dr. J. Trenton McClure, Professor of Large Animal Medicine at Atlantic Veterinary College (AVC) points to the top of the graph that shows tetracycline use in humans versus animals. This graph shows that there were significantly more kilograms given to animals than humans, from which the reader could infer that many more animals are being given antibiotics.

But the total kilograms of an administered antimicrobial is not an accurate way of assessing use. The number of doses administered depends on the weight of the animal and the drug it is being given. This is a more important parameter as it is the drug concentration that determines antimicrobial activity and influence on bacteria.

Also, the type of drug in the chart with the heaviest use in livestock was only of medium importance to human health, while the antimicrobials critically important in human medicine had the majority of use in humans, and very low use in animals.

Deciding, based on this graph, that way more animals than humans are being medicated is inaccurate. The data might indicate tetracycline could be the most therapeutically and cost-effective medicine available to farmers, so they’re more likely to select this for treating animals over other antimicrobials. Dr. McClure said that sensitivity data show there are a lot of food animal bacterial pathogens that are still sensitive to tetracyclines, while conversely there is more resistance in human pathogens, thus a physician may prescribe a more effective drug to their patient.

The volume of drug per kilogram of body weight required to kill the offending organism may be lower for human treatment.

For the veterinarian, selecting tetracycline over a potentially more potent medicine means that to kill the pathogens they use a significantly larger volume. The animals being treated (with the exception of poultry) can also weigh many times a human’s weight.

“Between antimicrobial drugs there are different doses because these antimicrobials have different concentrations in which they are effective,” said Dr. McClure. “Thus measuring total kilograms of drug A used compared to kilograms used of drug B is inaccurate as the effective daily dose may be 10 to 20 times higher for one drug over another… another reason why looking at animal doses is important.

“What is difficult about tetracycline is when it is dosed in feed as a growth promoter or preventative for disease, the dose is lower than the therapeutic dose and a group of animals are exposed. So it is difficult to come up with one standard way of measuring this. You would need to have good animal treatment records and funding to support the scientist to analyze this to come to useful conclusions.”

- CANADA’S AGRICULTURE DAY 2020 - February 10, 2020

- ROASTING ON PEI - November 1, 2019

- THE SALTY CHEF - October 1, 2019

- A YEAR LATER, STILL COOKING - August 1, 2018

- SPRING FESTIVAL FOOD - February 1, 2018

- Grandma Phoebe’s Mustard Pickles - November 1, 2017

- Namaste Lamb, Fall Flavours September 23, 2017 - September 25, 2017

- Lobster Party on the Beach 2017 - September 10, 2017

- Oysters on the Pier 2017 - September 10, 2017

- Going the Extra Mile While Buying Close to Home - September 1, 2017