Despite being ‘Canada’s Food Island’, PEI faces challenges with food security

Food and shelter: two of the most basic needs a person has. Imagine having to choose between them. Unfortunately for a number of Islanders, that is a choice that they sometimes have to make.

In a 2014 survey, 8700 households¹ in PEI were deemed food insecure. With 15.1 percent of the Island population dealing with some type of food insecurity, PEI ranked fifth in Canada and tied with Nova Scotia as having the third highest percentage of children living in food insecure households (22 percent). Although more recent figures are not yet available, Mike MacDonald, director of the Upper Room Food Bank in Charlottetown has seen a substantial increase in the food bank’s use just this past fall.

“Since September we have seen some major increases when we compare to the same month a year ago,” MacDonald said. “We’re certainly hoping that doesn’t continue, but we’ve seen an increase of about 40 families in September and 50 in October. December was 100.”

When asked if he has any idea on why there’s been such an increase, MacDonald hypothesized that the cost of housing may be part of the issue. “There’s different reasons for everybody but one of the main ones that we hear is the cost of housing. Everything seems to be going up in price, whether it’s food…just the cost of living in general.” MacDonald has been with the Upper Room Food Bank for 19 years, and over that time, he has seen the need for the food bank’s services grow.

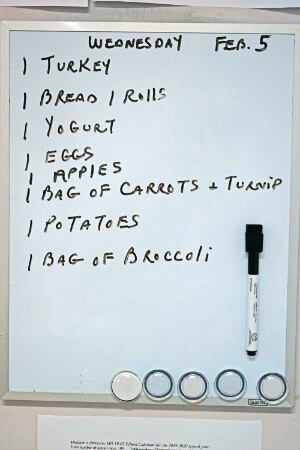

for distribution at the Upper Room Food Bank photo credit: Cheryl Young/Salty

Lindsay Smyth² has experienced food insecurity first hand. She agrees that the cost of housing in PEI is a large contributor to food insecurity. “In the current context, something that’s very important, is the cost of housing…and it is contributing largely to food insecurity on the Island right now,” Smyth said. “When you have folks who have to spend 40, 50, 60 percent of their income on rent, you can guarantee that the first thing that’s getting sacrificed is food.”

As the oldest child of four, Smyth’s father raised her and her siblings on his own. “I remember very vividly like around Christmas time, people would come to our door and they would have boxes and boxes full of food, turkeys, non-perishables, all that kind of stuff and I was kind of like as a kid, ‘Holy crap, these people are so great, we have all this food.’ Because generally it was tough to be a single parent and to make sure that your mortgage was paid, your lights were on etc,” she recalled.

“A lot of times I remember my father being like, ‘No, no I don’t need this, we don’t eat this much food’. I think there’s a lot of stigma and a lot of shame around it but in the really tough years he accepted it. And we would go through and we would take what we need. And then he would pile us all into the car and we would go deliver the things we didn’t need to other people who needed it. Once I was old enough to kind of understand what that was, I knew that we had lived on the margins.”

Smyth has worked hard to move past those margins, and the difficulties she faced in school due to hunger. As the oldest child she tended to give any available food to her younger siblings. “I went to school and I hadn’t eaten breakfast. And I didn’t have lunch. So I would generally eat at supper time when I got home,“ she recalled.

The lack of quality nutrition affected her grades, but despite the challenges she faced in high school, she was able to get a higher education and will soon graduate with her masters degree. The lasting effects of being food insecure still linger with her however, and even with a reasonable income now, she still has to remind herself “okay, when I get a paycheque, I have money for food.”

receive at the Upper Room Food Bank photo credit: Cheryl Young/Salty

Poverty is obviously a root cause for food insecurity and multiple studies and research link the two. Matthew MacDonald works with the Native Council of PEI as a policy analyst. “There are a lot of families that are struggling,” he said.

He sees how food insecurity and annual household income go hand in hand with Indigenous people. A report commissioned in 2017 by the Council found that 59 percent of the respondents who were living off-reserve recorded an annual income of less than $40,000 for their household, with 24 percent of them reporting poor health. “The lower your income, the more likely you are to report poor health,” he explained.

Living on the margins is typical for many Islanders who are food insecure. The Upper Room Food Bank is the largest of PEI’s six food banks, and as such they see the most people come through their doors looking for assistance. Mike MacDonald estimates that this time of year the food bank will often serve 540 to 550 families a month. The food bank system allows one visit per month per household.

Along with the cost of housing and poverty as a root cause for food insecurity, MacDonald also points to PEI’s seasonal employment opportunities as part of the reasons for food insecurity. “A lot of people who use our services are employed seasonally. Then of course, you know, some of the winter months and you know, they’re relying on EI in that time, but a lot of our clients as well are on social systems.”

Vivian Dourte and her husband Frank Dourte run the Montague Food Bank, volunteering their time each week to help families in that area get food. She agreed the seasonal aspect of many PEI jobs is problematic.

“You’re working your 16 weeks or whatever, if you’re only working minimum wage, by the time you collect EI, you’re only getting 55 percent of whatever you are making, right? So it doesn’t even match and people are running out of their EI before the next season starts. And so we’re going to see an increase starting now until the end of April because people’s EI cuts out.”

Dourte also was in agreement about housing costs contributing to food insecurity. “If you can find a place to rent, it’s probably like $800. And then you have to pay for utilities on top of that. And if you’re only getting, you know, 15-20 hours a week at work, you can’t make it. If you’ve got kids and you’ve got daycare…everything just kind of adds up and people just go deeper and deeper in the hole. And, you know, people who are on social services, they’re only allotted $550 a month for rent. So if their rent is $800 they’ve already spent their whole cheque on rent and they have no food or anything left for the rest.”

Smyth is blunt about common misconceptions that many have with regards to people working minimum wage jobs. “I’d like to take some time to kind of dispel that myth of like, if you’re working a minimum wage job, ‘well just get a better job. Go get an education, get a better job’. Let me be an example that I have spent a decade, piss poor.

“I have a bachelor degree, I will have a masters in a few months. And I have done nothing but work since I left home. So this whole notion of, ‘you’re not working hard enough, you’re clearly not putting in enough effort, your education obviously failed’, it’s all bullshit.

“Not to mention, what’s your take home [pay] but what is your mental health? Your whole quality of life is just shot, because you don’t do anything else. I mean I’m now fortunate, like I said, this is my first time ever in a job not earning minimum wage, and it is so strange to me to get a paycheque and not have the entire thing just go towards rent.”

Food insecurity is a complex issue, and there does not seem to be a simple solution. A basic income guarantee (BIG) is currently being discussed with the provincial government. Many different advocates, community groups, and charities are participating in the Legislature’s special committee on poverty presenting their thoughts and ideas.

The committee will continue to explore exactly what a BIG program could look like for PEI and hope to have a report later this year. With the highest social assistance rates in the Maritimes (PEI currently has 3400 households reliant on assistance), a BIG program may potentially be a solution.

In 2019 the PEI government increased the food allowance portion of social assistance by ten percent, and announced an additional increase of approximately $6.4 million to overall social assistance rates beginning in January 2020.

The government is also transitioning to a single living allowance system, which will allow social assistance clients more autonomy and the flexibility to personally budget their money for food, housing, and other living expenses.

These measures, along with other research being done across PEI, appears to show a political will to examine food insecurity and its causes, and to ensure that Islanders don’t have to choose between a roof over their heads, or food on their table. Time will tell.

¹Data Source: Statistics Canada, Canadian Community Health Survey (CCHS), 2014

²Name has been changed to protect identity

PEI FOOD RESOURCES

Here are some food resources across PEI. Please note that is not a definitive list.

Charlottetown/Queens County

• Upper Room Food Bank (33 Belmont St)

• Upper Room Soup Kitchen (101 Richmond St)

• Salvation Army Food Bank (203 Fitzroy St)

• UPEI Food Bank (Chaplaincy Centre)

• Cornwall Upper Room Satellite Food Bank (29 Cornwall Rd)

• Community Outreach Centre (211 Euston St)

• South Shore Food Share (20424 Trans- Canada Highway, Crapaud)

King’s County

• Montague Food Bank (567 Main St)

• Montague Soup Kitchen, Montague Church of Christ (513 Main St)

• Souris Food Bank (56 Main St)

Prince County

• Salvation Army Prince County Food Bank (299 Pope Rd, Summerside)

• Salvation Army Soup Kitchen (299 Pope Rd, Summerside)

• Tignish Caring Cupboard (210 Maple Street, Tignish)

- WTF - December 2, 2020

- WHAT GOES AROUND COMES AROUND - June 12, 2020

- Salty’s 2020 Gift Guide - December 2, 2020

- A RETURN OF DELIVERY - May 6, 2020

- ICYMI - April 22, 2020

- NEW BIOMASS BOILERS FOR LOCAL GREENHOUSE - March 31, 2020

- TOP CHEF CANADA COMPETITOR FROM PEI - March 4, 2020

- FOOD INSECURE - March 1, 2020

- ACCESS TO FRESH PRODUCE - March 1, 2020

- POLITICS OF SCHOOL FOOD - March 1, 2020